One of the unanticipated side effects of the seismic COVID-19 pandemic has been how it shed light on a community long consigned to the shadows—the several million people around the world living with leprosy.

Kalaupapa:

Hawaii’s Leprosy Colony on Molokai

Photo by SeaSideWithEmily.com

This occurred in the news recently when the last county in the United States to get COVID-19 was shown to be located on a remote Hawaiian outpost and former leper colony.30

The media exposure brought heightened attention to World Leprosy Day on January 24, an annual awareness initiative supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under the “Bust the Myths, Learn the Facts” banner aiming to dispel the misinformation that keeps the disease shrouded in fear.31

Leprosy: Bust the Myths, Learn the Facts

Despite the fact that around 95 percent of the world’s population has natural immunity to the disease, leprosy patients continue to face unfounded discrimination.32 For example, in parts of South Asia, more than 100 laws restrict the rights of people with leprosy, including barring them from running for local office.33

Despite the fact that 95% of the world’s population

has natural immunity to the disease, leprosy patients continue

to face unfounded discrimination.

Nor is leprosy as contagious as is widely believed. A study in Bangladesh found that less than two percent of those who shared a home with someone with leprosy would contract the disease themselves, “which is a reminder that there is no need to isolate people affected by leprosy.”34

But that hasn’t curbed the shunning and shaming of leprosy patients, who are often forced to leave their communities and reduced to begging.

Geographical distribution of new cases of Hansen’s disease reported to WHO in 2019.

Source: World Health Organizaion/National leprosy programmes © World Health Organization (WHO), 2019. All rights reserved.

Throughout History, People Believed to Have Leprosy Were Among the Most Reviled

Photo by Amazon.com

Surprising to many is that the United States had its own leprosy colonies until not too long ago. The largest, in Hawaii, closed in 1969 after taking in more than 8,000 patients over its lifetime, while the last, in Louisiana, where patients weren’t allowed to vote or marry,35 was shuttered in 2015.36 Around 200 new cases are still reported in the United States each year, most among people who have spent time in parts of the world where the disease is more prevalent.

At one stage, a century back, the assistant surgeon general declared there were “1,200 lepers at large” in America, seeking permission to round them up like criminals, recounts journalist Pam Fessler in her book, Carville's Cure: Leprosy, Stigma, and the Fight for Justice. It tells the story of the Louisiana leprosy colony and her husband’s grandfather, who ran away when he was diagnosed with the disease to avoid being confined.

“Throughout history, those believed to have leprosy… were among the most reviled members of society, outcasts sometimes believed to be sinners who brought the illness upon themselves,” says Fessler. “Even today, the threat of leprosy is used to demonize immigrants and people living in homeless encampments as potential carriers of the disease—although there's no evidence that's true.”37

Eliminating Discrimination and False Conceptions Surrounding Leprosy is Key to Eliminating the Disease Itself

Photo by GFA World (GFA World)

As a previous Gospel for Asia (GFA) special report underscored, eliminating discrimination and false conceptions of leprosy is key to eliminating the disease itself. For, while effective drug treatments have been available since the 1980s, ongoing stigma means many sufferers wait too long to be diagnosed, causing irreversible damage. Meanwhile, clinical trials on a vaccine are continuing.

The coronavirus-fueled renewed focus on this largely forgotten disease has been two-edged—revealing how much deep-rooted ignorance and prejudice still has to be overcome while also offering hope for greater compassion, and even possibly a reduction in its incidence.

COVID-19 Causes Setbacks for Existing Leprosy Patients

As authorities struggled to know how best to respond to the COVID-19 crisis in the first part of 2020, it was all too common to find those who contracted the virus likened to “lepers”—a fear-mongering and dehumanizing reference to those with leprosy (Hansen’s Disease).

For example, when Italy began looking to reopen after a significant lockdown prompted by a high coronavirus death toll, the country’s foreign minister, Luigi Di Maio, commented, “If anyone thinks they can treat us like a leper colony, then they should know that we will not stand for it.”38

Photo by Presidenza della Repubblica

In Australia, former television presenter Sam Newman commented that people in Melbourne, which introduced some of the toughest COVID-19 restrictions in the country, were “living in a leper colony.”39

Meanwhile, in England, when television doctor Hilary Jones was asked whether it was safe to visit Birmingham, a city where cases had spiked, he answered “‘it’s not like a leper colony or anything.”40

While such comments reveal some of the deep-seated alarm still aroused by the disfiguring condition, it’s also been suggested that lessons learned from the coronavirus could lead to leprosy rates being drastically reduced in South Asia—one of the areas where it remains most prevalent. During the pandemic, wealthy people in cities wouldn’t allow domestic help to come to their homes from where they lived in the slums for fear of COVID-19 infection. It is hoped that this dynamic will further expose the health disparity between rich and poor, maybe prompting a renewed effort to end the inadequate living conditions that incubate the disease.41

People with leprosy have to deal with two crippling challenges—

the lack of pain caused by deadened nerves that results

in deforming injuries and the unseen internal pain

they experience because of prejudice.

First, however, there will be a need to overcome the setback for existing leprosy patients caused by the pandemic. The lockdown across Asia meant many patients were not able to access the regular treatment required to treat them successfully, according to one group of researchers.42 Another study43 found people with leprosy were at higher risk of contracting COVID-19, in part because of the difficulty they had in maintaining personal hygiene due to deformities and lack of money for soap and sanitizers.

Dr. Mary Verghese,

Executive Director of The Leprosy Mission Trust India (TLMT)

Photo by The Leprosy Mission

The pandemic impacted leprosy patients more than any other vulnerable group, said Dr. Mary Verghese, executive director of The Leprosy Mission Trust India (TLMT). According to Dr. Verghese, “People affected by leprosy are one of the most marginalised sections of society.”44

60%

of those disabled by leprosy who were surveyed felt that life was “totally meaningless.”

Elsewhere, with the pandemic bringing leprosy renewed media exposure, it could also awaken greater appreciation for the plight of those ostracized because of their condition. After all, being confined to one’s own home for an extended period because of coronavirus concerns may be uncomfortable, but it doesn’t compare to being forcibly isolated for the rest of one’s life in a leprosy colony.

It’s easy to recognize that people with leprosy have to deal with two crippling challenges—the lack of pain caused by deadened nerves that results in deforming injuries and the unseen internal pain they experience because of prejudice. There has not been a lot of research into the disease’s emotional damage. However, a recent study in Bangladesh set out to quantify how it impacts sufferers personally and found 60 percent of those disabled by leprosy who were surveyed felt that life was “totally meaningless.”45

Because the pandemic has only worsened many leprosy patients’ isolation and economic hardship, one report in Nepal warned that it “may lead to increased loneliness among them, which may further affect their anxiety and depression level.”46

GFA World Doing What it Can to Alleviate the Difficulties of People with Leprosy

Aware that people with leprosy were being pushed even further to the fringes by the pandemic, GFA and other organizations already working among these outcasts did what they could to alleviate their difficulties.

Providing Basic Necessities

GFA workers distributed laundry detergent, soap and food aid to widows and leprosy patients.47 These provisions were especially helpful because many leprosy patients sustain their daily existence through begging, which became impossible when the lockdown meant they couldn’t leave their homes.

Giving Goats as Income-Generating Tools

Physical limitations preclude leprosy patients from some income-generating tools, but GFA has found a creative way to help them—giving them goats to raise. Goats offer a good solution for several reasons: They are fairly low-maintenance and easy to manage, they multiply quickly, and their kids and milk yield can provide a regular monthly income, eliminating the need to beg.

Helpful Care from Sisters of the Cross

GFA’s work in scores of leprosy colonies across Asia extends beyond meeting just practical needs, as important as that is. GFA’s Sisters of the Cross and members of local churches who visit the colonies on a regular basis also aim to touch bruised hearts.

Physical Compassion and Genuine Concern

In addition to providing income-generating help, food and clothing, GFA teams offer physical care that embodies the love of Jesus. It comes in the manner in which Jesus responded when a man suffering from a skin disease came asking to be healed. Jesus didn’t do so just with a word of command, as He could have. Mark 1:41 notes, “Jesus, moved with compassion, stretched out his hand and touched him.”

In the same way, GFA teams close the emotional gap that has separated so many people with leprosy from the rest of the world by literal hands-on care, such as tending for wounds. Patients at one colony were deeply touched when a visiting group shared a meal with them.48 It was “the first time people came and ate with us,” one said.

Among the residents of one of the leprosy colonies visited by Sisters of the Cross is Macia, who has lived there for more than 50 years, since contracting leprosy as a child. “Before the sisters came there was no one to help trim our hair or cut our nails, or help us clean our houses and encourage us,” she says. “The sisters help us by cleaning our wounds and they make us happy and encouraged all the time.”49

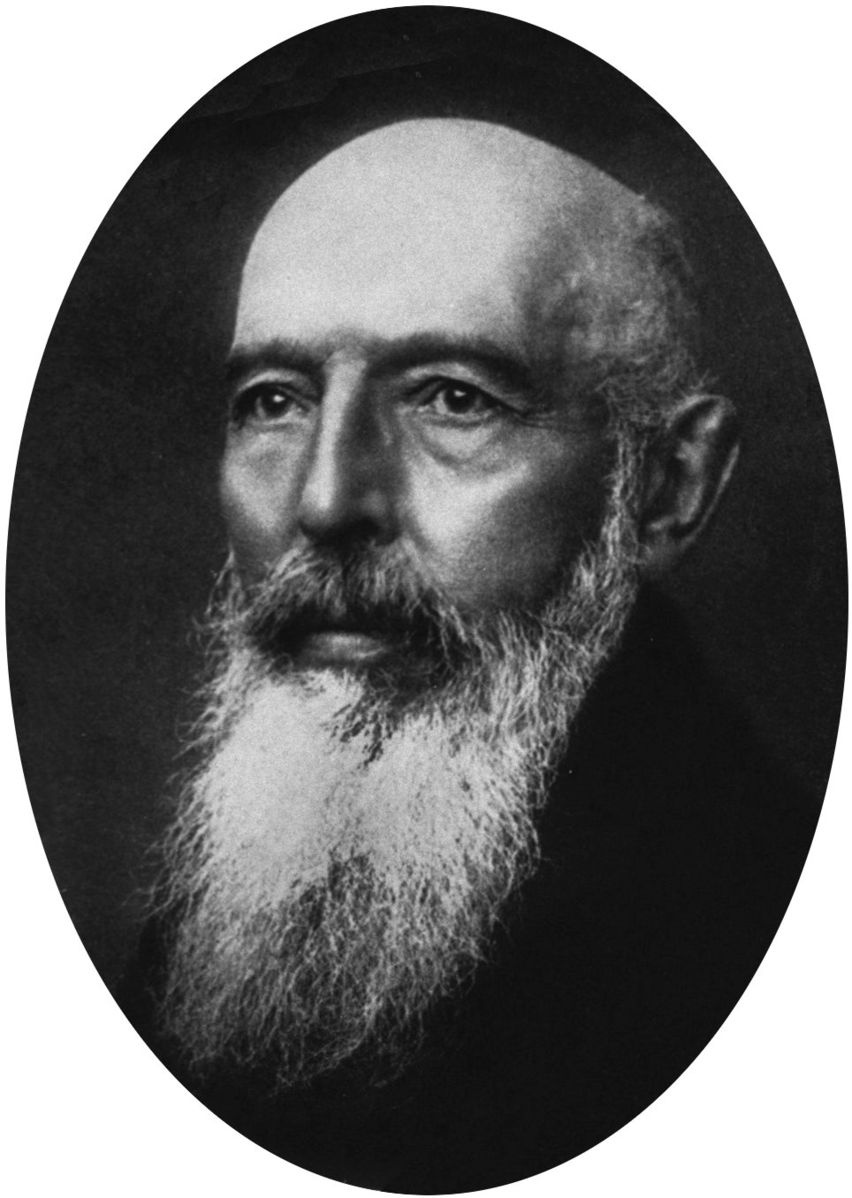

Dr. K.P. Yohannan,

GFA Founder

For GFA founder K.P. Yohannan, this incarnational ministry is “an example of how God works. He wants us, in our physical bodies, with hands, legs, eyes and ears, to live as Christ lived.”50

This ends the update to our original Special Report, which is featured in its entirety below.

Progress in the Fight Against Leprosy Leprosy Prevention is Key to Elimination

In 2018, another 208,619 new cases of leprosy were detected globally.1 Is any progress being made in the fight to eliminate leprosy?

In short, yes. Even detecting those new cases is one step closer to conquering leprosy. However, the fact that more than 200,000 people were diagnosed with leprosy reveals we still have work to do.

As discussed in GFA World’s previous Special Report, Leprosy: Misunderstandings and Stigma Keep it Alive, the fight against leprosy, also known as Hansen’s disease, has two main battlefronts. The first and most obvious is in the medical field: detecting and treating leprosy patients before they suffer permanent damage or transmit the disease to anyone else. The second battle line is equally important—and equally challenging: eliminating discrimination and stigma toward those affected by leprosy.

Global leprosy-elimination leaders are making exciting advances both medically and socially that are worth noting.

Sabita is a cured leprosy patient who does not presently suffer from her sickness. She is able to walk to couple of kilometers a day, and do basic tasks like making tea. Although leprosy caused deformation in Sabita's hands and body, it is completely cured now and she is experiencing life as a happy and content individual.

Medical Advances: Leprosy Prevention Is Key to Elimination

One of the great hindrances in eliminating leprosy is detecting and treating new cases before the infection spreads to others. Leprosy can take as long as 20 years to manifest physical signs of the infection2 and can spread to many vulnerable people during that incubation period. Additionally, because people with leprosy are frequently ostracized by society, many who suspect they have contracted leprosy will hide their condition, enabling transmission and going without the treatment that would save them from disfigurement.

Leprosy can take as long as 20 years

to manifest physical signs of the infection.

Multi-drug therapy (MDT) treatment has successfully cured leprosy patients since the 1980s, but it is not preventative in nature. The treatment does eliminate any chance of transmission in cured patients, but that alone cannot eliminate global leprosy due to the number of people who hide their condition. MDT also does not reverse any damage caused by the disease, so impacted nerves or wounds experienced from nerve damage remain as evidence of the patient’s traumatic health issue. Treatment must be provided prior to disfigurement in order to avoid these physical effects of leprosy.

For these reasons, preventing and quickly detecting new cases are vital partners to the established MDT treatment.

Photomicrograph of a skin tissue sample from a patient with leprosy reveals a cutaneous nerve invaded by numerous Mycobacterium leprae bacteria. Photo by Arthur E. Kaye, CDC

A Vaccine for Leprosy

A new player for leprosy elimination is on the horizon: a leprosy vaccine. American Leprosy Missions (ALM), a Christian organization focusing on aiding those impacted by neglected tropical diseases, is 17 years into its partnership with the Infectious Disease Research Institute to develop the world’s first leprosy-specific vaccine.3 The vaccine, LepVax, has proven hopeful during the development process and is currently being tested among volunteers in a leprosy-endemic area.

In its recent report on the Phase 1a clinical trial, ALM writes, “We believe this leprosy vaccine will be an exciting new way to stop the transmission of leprosy and the only way to protect people long term. What’s more, the vaccine may protect against nerve damage among those already diagnosed with leprosy, the most serious complication of leprosy.”4

If people living in areas with high rates of leprosy received a leprosy vaccine, new cases could be avoided—an incredible landmark in global leprosy elimination. This promising vaccine is projected to be in Phase 1b clinical trials for another two years before moving on in the development process.

Preventative Medication

Another exciting new shift in the world of leprosy is the use of preventative medication for those at risk of developing leprosy. This relatively new practice takes one of the drugs used in the MDT treatment, rifampicin, and administers it to people in frequent proximity to those with leprosy, such as family members of leprosy patients or those living in endemic areas.

ALM provided 7,091 pounds of critical medicines and supplies to Ghana partners. Photo by ALM

This single-dose rifampicin (SDR) treatment reduces people’s risk of developing leprosy by 60 percent,5 whether or not they have previously been exposed to the disease. It is not a magic cure—success rates vary among the different kinds of leprosy, and protection only lasts a few years—but it has an additional benefit. Providing this treatment for those at risk of contracting leprosy also enables medical workers to discover early cases of leprosy in people who might otherwise not be examined.

The stigma around leprosy, however, has barred the way for medical treatment in many areas. Many people still hesitate to do anything in connection to leprosy treatment, even if it is preventative.

Resources to overcome challenges like this were presented during the 20th International Leprosy Congress. In September 2019, more than 1,000 people from 55 countries gathered in Manila, Philippines, for the Congress. There, scientists, practitioners and leprosy advocates shared research, ideas and resources to further their goal of zero leprosy.

During the Congress, the Global Partnership for Zero Leprosy launched the Best Practices Zero Leprosy Toolkit,6 designed to “support countries in their work towards ending leprosy and its associated disabilities and stigma.”

Just one of the valuable resources this kit contains is advice on how to prepare communities to be favorable toward receiving preventative SDR.

Medical personnel found that performing pre-treatment counselling in communities promoted willingness toward participation in the SDR preventative treatment. Education about leprosy made 90 percent of those in close connection to leprosy patients willing to participate in the treatment.7

Leprosy: A Human Rights Issue

Advocates for zero leprosy are active on the social battle-front as well. The shunning and discrimination experienced by people with leprosy are gradually being recognized as an issue of human rights, not only the result of a medical problem, which means appropriate actions can be taken to combat the issue.

Leprosy is not a hereditary disease, which is why many children born to leprosy parents are healthy. But the risk of contacting leprosy from their family member is very high due to living in a close proximity.

Alice Cruz, UN Special Rapporteur, speaks out boldly against the abused rights of people affected by Hansen’s disease.

“Persons affected by leprosy and their families have been subjected to serious human rights violations,” she says. “They have been denied their dignity and their basic human rights; subjected to stigmatizing language, segregation, separation from their families, and separation within the household, even from their children.”8

Alice and many others are calling upon nations to take action on behalf of leprosy-afflicted individuals and their families, making it known that social rejection of leprosy patients is needless and unacceptable.

Groups such as the Global Partnership for Zero Leprosy9 and International Federation of Anti-Leprosy Associations (ILEP)10 are working at an international level to eliminate leprosy, in part by changing the way people with Hansen’s disease are perceived by society.

ILEP maintains careful watch on the 136 policies globally that promote or enable discrimination against people afflicted with leprosy and seeks to help those policies change. These legislations11 range from permitting divorce and expelling students from universities to requiring that individuals with leprosy be deported. It’s hard to believe that people infected with a completely curable disease can be legally deported in parts of the world, but that is the reality of the extreme fear and stigma linked to leprosy.

Social rejection of leprosy patients is needless and unacceptable.

In addition to seeking changes in laws regarding people with Hansen’s disease, ILEP is also influencing people’s everyday approach to leprosy. When writing about leprosy and the people whom it affects, they adhere to strict guidelines as to the terminology, imagery and photography used. They reach out to media sources to encourage them to alter their pieces to ensure that people with leprosy are treated with respect and dignity. ILEP challenges everyone to do the same,12 even providing samples of how to respectfully request someone to change their terminology.

Eliminating Stigma on a Personal Level

Legislation regarding how society should interact with people with leprosy is extremely important, but even so, changing deeply ingrained attitudes is ultimately up to the individual; a law cannot create love in a person’s heart toward others. Each person must overcome obstacles on a personal, intimate level—and Jesus can help them do that.

Gospel for Asia-supported workers have been showing love and respect toward leprosy patients for decades.13 Their love for Jesus helps them overcome their cultures’ normal attitudes toward those with leprosy, and now they serve as powerful examples to many communities across Asia.

Workers at a GFA-supported hospital for leprosy patients witness on a daily basis the emotional needs of people afflicted with Hansen’s disease. When asked how patients respond to the kindness demonstrated by hospital workers, GFA’s field correspondent explained that deep bonds frequently develop. The patients receive their caregivers as sons and daughters, welcoming them into their lives in place of the biological family that spurned them. Being seen for who they are and not what disease they have gives these patients courage to press on and live a life with hope.

All the hospital staff at the GFA-supported Medical Clinic exist and function with a purpose to help the poor and needy, including leprosy patients, through our medical facilities.

At a medical camp organized to bless a leprosy colony in another part of Asia in honor of World Leprosy Day, children from a GFA-supported Child Sponsorship Program center performed a skit for the colony residents. These children are learning from a young age to respond to leprosy patients with compassion rather than with fear, with kindness instead of rejection. Most of the people living in this colony had already been cured of leprosy, but their damaged limbs caused their society to spurn them anyway. Although their families and society reject these leprosy patients, these children and national workers showed them the dignity they deserve as human beings bearing God’s image.

Each person who gains an honoring viewpoint toward those afflicted with leprosy is another voice for change, one more compassionate heart to aid those in need and one more step bringing us closer to eliminating leprosy.

Through the diligent efforts of scientists, medical workers, policy makers and compassionate citizens around the globe, we see exciting new advances in the fight against leprosy. The battle is not yet won, but we are better equipped to press in and overcome this devastating disease.

A speaker at the International Leprosy Congress summarized the global leprosy situation well: “The last mile in the work of leprosy, it can be accomplished. We absolutely can do this, but we can only do it together.”14

What can you do to help eliminate leprosy?

- Pray for successful preventative medical treatments.

- Lift up the GFA-supported workers and all the other men and women who are helping change society’s perception of those afflicted with leprosy.

- Financially support the efforts of organizations working to eliminate leprosy, such as GFA World (GFA) and ALM.

- Be a positive voice toward those with Hansen’s disease.

- Encourage others to partner with organizations serving people afflicted with leprosy.

We live in an amazing era where eradicating devastating diseases is possible. Let’s celebrate the triumphs already won in the fight against leprosy and press on toward global leprosy elimination!

This ends the update to our original Special Report, which is featured in its entirety below.

Leprosy: Misunderstandings and Stigma Keep it Alive Although It’s a Curable Worldwide Problem

Leprosy. For many, a cloud of mystery, fear and shame surrounds this disease. It’s a disease that destroys nerves and deadens limbs to sensations of touch or pain, yet at the same time can trigger bouts of unbearable agony for the sufferer as infection exposes raw bones. It’s a disease that is difficult to contract, yet carries a stigma so strong that leprosy-affected people have been forced into isolation for centuries. Why is this disease so feared, and how can we help those who contract it?

What is leprosy?

Mycobacterium leprae bacteria

(Public Domain)

Leprosy, otherwise known as Hansen’s disease, is an infectious disease caused by a bacteria called Mycobacterium leprae. This chronic nervous system disease “mainly affects the skin, the peripheral nerves, mucosal surfaces of the upper respiratory tract and the eyes,” according to the World Health Organization15. The first symptoms of leprosy are often eye damage, painless ulcers or patches of discolored skin with accompanying numbness in the affected area. Without intervention, leprosy may cause crippling of hands and feet, loss of limbs, tissue loss on the face and blindness.

The bacteria slowly attacks the nerves and will leave the one affected without the ability to detect pain. Their hands and feet will no longer notice the hot pot burning their palms, the sharp object penetrating their skin, or even a dislocated ankle as they go about their daily life. Wounds become infected, and tissue loss, degeneration or even amputation follows.

The physical disfigurement caused by leprosy is one of the most well-known signs of the disease.

The physical disfigurement caused by leprosy creates a physical and emotional barrier between the individual and the rest of society, the United Nations16 explains.

Hansen’s disease, as we know it, has mutilated lives for thousands of years. Reports of leprosy go back as far as 600 BC.17 In the Old and New Testament, the Israelites received instructions from God to remove leprosy from among their camp; and later, Jesus Himself touches and heals many people afflicted with leprosy.

Are there any differences between modern-day leprosy and the mentions of leprosy in the Bible?

Answers in Genesis (AIG), an apologetics ministry that provides answers to many questions about the Bible and topics like creation and science, released an article18 about biblical leprosy. The article, condensed from The Genesis of Germs by Dr. Alan Gillen, states, “Biblical leprosy is a broader term than the leprosy (Hansen’s disease) that we know today. The Hebrew tsara’ath included a variety of ailments and is most frequently seen in Leviticus, where it referred primarily to uncleanness or imperfections according to biblical standards. A person with any scaly skin blemish was tsara’ath. The symbolism extended to rot or blemish on leather, the walls of a house, and woven cloth.”

Many have believed the disease is the result of some great sin of the victim.

It is likely that the man with a withered hand in Mark 3:1–5 suffered from the leprosy we are discussing today. Cultures around the world have recorded the devastating effects of Hansen’s disease: disfigured noses and facial tissue, blind eyes, missing fingers or toes, and hearts rent in grief and anguish.

Intensifying the trauma of the disease is the weight of guilt many sufferers carry. Over the centuries, many have believed the disease is the result of some great sin of the victim. Instead of kindness or pity, the human being—whose world has just shattered—receives a cold shoulder; a fearful stare; an invitation to hit the road, move to a “leper colony” and leave the life they knew before.

Leprosy is Curable—But Still Feared

For hundreds of years, even medical professionals responded in fear of the infectious disease. Because of the misunderstandings and stigma associated with leprosy, very few people in history chose to study the bacterial infection. The few who did confront it now have millions of people benefitting from their courageous efforts.

Dr. A. Hansen, the man who discovered the bacteria that causes leprosy

(Public Domain)

In 1873, when people believed leprosy was the result of a curse or a judgement from the gods, Dr. A. Hansen, a physician from Norway, discovered that leprosy was caused by bacteria. He proved it was a contagious disease, like so many other plagues in our world. And when you find the cause of a disease, there is hope of finding a cure.

After that, a few remedies were found to treat leprosy patients, but the disease and its progression remained widely unknown and unexplored until the 1940s. At that time, new anti-leprosy drugs called sulfones were used to treat patients of Hansen’s disease, but after the bacteria was eliminated from the person’s system, the disfigurement remained—and the discrimination.

In 1947, a world-renowned orthopedic surgeon working in India, Dr. Paul Brand, visited a leprosarium. Dr. Brand was appalled to uncover the lack of research performed regarding the physical deformation leprosy causes. In his book The Gift of Pain, coauthored with best-selling writer Philip Yancey, Dr. Brand records a conversation he had with a pioneer leprosy specialist, Dr. Bob Cochrane, at a leprosy sanitarium.

Dr. Paul Brand, who developed breakthrough treatments for leprosy

(Photo credit The Leprosy Mission)

Dr. Brand learned from Dr. Cochrane that, although leprosy was crippling more people than polio or any other disease, few physicians had investigated the disease, and no orthopedist had researched leprosy and the disfigurement it produces. Most doctors at that time joined society in thinking leprosy was a curse from the gods, and as such, it was not a disease they paid attention to.

That conversation and many future encounters with leprosy patients spurred Dr. Brand to delve into the disease and to later become a leprosy specialist himself, establishing breakthrough techniques for correcting leprosy disfigurement.

Although most in the medical field steered clear of leprosy for hundreds and even thousands of years, some dedicated men and women throughout history have labored to understand leprosy. As a result, today leprosy is curable.

Over the decades following Dr. Hansen’s discovery in the 1870s, multiple treatments were used, but they achieved varied success and leprosy bacteria began developing an immunity to the sulfone drug therapy. Finally, in the 1980s, a multi-drug therapy (MDT) treatment successfully cured leprosy without the threat of bacteria developing an immunity, and WHO adopted it as the standard leprosy treatment.

With this powerful cure, multiple global leprosy-elimination strategies have been implemented and have made great strides in reducing new leprosy cases. With support from groups such as the Nippon Foundation, Novartis Foundation and others, MDT has been globally available since 1995—free of charge.

Many leprosy patients like Rushil make their living by begging, and they often can’t afford to buy certain medications that they need. Rushil (pictured) is very grateful for GFA-supported workers providing medicines for free. Read more of Rushil’s story »

Yet in 2015, more than 200,000 people discovered they had leprosy—a disease that not only ravages the body but also tears families and communities apart.

Now that we have a cure for leprosy, why then, does this devastating disease still exist in our world?

Yohei Sasakawa, the WHO ambassador for leprosy elimination and the chairman of the Nippon Foundation, gives the answer to this question.

“A leprosy campaign can be likened to a motorcycle,” Sasakawa says. “The front wheel is the medical cure, and the rear wheel is the elimination of stigma and discrimination. The motorcycle will not run smoothly unless the two wheels are balanced and moving at the same speed.”

It is the stigma and misunderstanding surrounding leprosy that causes the disease to still ravage lives today. Eliminating discrimination and false conceptions of leprosy is key to eliminating the disease itself.

Stigma Hindering Leprosy Prevention

GFA World’s field correspondents have interviewed many leprosy patients over the years. Each person’s account is unique, but there are common elements: shame or fear hindering them from seeking medical attention; believing treatment is too costly; and excommunication from family or friends when it becomes known they contracted leprosy. Even the children of leprosy patients are spurned from society.

Precious stories of faithful husbands standing by their leprosy-affected wives19 shine like beacons in a bleak sea of sorrowful testimonies.

When Kishori contracted leprosy, her husband stood by her—a counter-cultural decision in a society that usually rejects people afflicted with leprosy.

Read why Kishori smiles today »

When leprosy was discovered in Kishori’s body, her community endangered her marriage.

“Why are you keeping this sick person with you?” Kishori’s neighbors questioned her husband. “You can send her to her mother’s home.”

“How can I leave her?” he replied to his neighbors. “I love her.”

Kishori’s husband stood by her faithfully, never heeding their community’s call to abandon her because of her leprosy.

Stories like Kishori’s reveal the strength of ingrained stigma—but also how love can withstand those pressures. Sadly, more frequent are the stories of men and women abandoned by their spouses, in-laws, or even kicked out of their homes by their children.

“Women are particularly vulnerable to the myths and stigma associated with leprosy and suffer higher social costs of leprosy owing to fewer options open to them,” sites The World Bank in a document for India’s Second National Leprosy Elimination Project20. The report adds that, although women comprise 25 percent of leprosy patients, because of strong cultural protocol traditions regarding interactions between men and women “it is more difficult for the service providers and public health information campaigns to reach them.”

Once on their own, men, women and even children of all ages often gather together in leprosy colonies. There, at least, they are understood by their neighbors who suffer from the same affliction. In these leprosy colonies, governments often organize relief and medical work for patients. Yet many find the monthly ration too meager to live on, and they must do whatever they can to keep themselves and any family members with them alive.

Cultural stigma and misunderstanding oftentimes force leprosy sufferers to live in a community by themselves.

Here again, stigma bars their way. Dr. Brand shares in The Gift of Pain the story of Sadan, a leprosy patient whom his wife met. Leprosy had first appeared on Sadan’s body when he was only 8 years old. The stigma of his disease meant he was expelled from school and isolated from society. The child’s friends avoided him, even crossing the street to keep from encountering Sadan. Finally, when he was 16 years old, Sadan managed to attend a mission school, but his education couldn’t cover up his disease. Employers turned him down, and restaurants and stores would have nothing to do with him. Even public transportation was denied him.

The deformed hands of leprosy patients—and the stigma that surrounds the disease—limit job opportunities.

Many unheard stories follow a pattern similar to Sadan’s. The jobs available to leprosy patients are few, and their damaged hands and feet limit them even more. Some may be able to open shops within their colony—few patients dare to venture out to public markets for fear of disturbing other customers or shop owners with their presence—while others turn to begging, utilizing the very deformities that trapped them in such desperation.

Pervasive fear of catching leprosy permeates the minds of those around leprosy patients, but the reality is that 95 percent of people are naturally immune to leprosy.21 Only those who lack this inborn immunity can contract the disease. Research has made great strides in learning about leprosy, but how leprosy is transmitted from person to person is still largely unknown. Those who develop leprosy are typically people who have been closely exposed to Hansen’s disease for an extended period of time, such as children—who appear to be especially vulnerable.

As stated before, leprosy is curable; but too few people know this life-changing fact. Believing there is nothing to be done or that treatment is too expensive to obtain, those who could be cured of their disease hide in secret, waiting for the “unavoidable” day when sores and disfigurement announce them as “lepers.”

Yet with even one dose of MDT, leprosy patients are no longer contagious, according to American Leprosy Missions.22 Depending on which of the types of leprosy they contracted, they can be cured with six to twelve months of proper treatment23.

"A leprosy campaign can be likened to a motorcycle," Sasakawa says. "The front wheel is the medical cure, and the rear wheel is the elimination of stigma and discrimination. The motorcycle will not run smoothly unless the two wheels are balanced and moving at the same speed."

The key is detecting leprosy early enough to avoid the debilitation of leprosy as it runs its course—and to prevent the patient from transmitting it to anyone else.

“The problem with leprosy [elimination],” says a GFA-supported worker involved in leprosy ministry, “is [that] young people, when they identify or when they come to know that they are affected with leprosy, they hide, because there is a fear that if they disclose [their disease] they will be sent out from their families and they will be sent out from their villages. That happened in the past, and it happens even today.”

Dr. Poonam Khetrapal Singh, WHO regional director for South-East Asia24, confirms the self-perpetuating effect of stigma, not just among youths but of people of all ages, saying, “As long as leprosy transmission and associated disabilities exist, so will stigma and discrimination and vice-versa.”

Yet beyond the fear of rejection, there is another force at play hindering patients from seeking help: an unwarranted sense of guilt.

Sakshi, who ministered to leprosy patients, once had leprosy herself before Jesus healed her.

Misunderstanding Leprosy: ‘I Deserve This Disease’

Sakshi was rejected by her family when, as a teenager, she found out she had leprosy. Read her story »

“Don’t open my bandage!” the leprosy patient cried out. For years the patient believed it was because of their sin that the destructive disease controlled their body. Now, they thought they must suffer and settle with bearing it alone.

But after the leprosy patient’s exclamation, Sakshi, a GFA-supported missionary, revealed her own hands and feet to the patient, deformity clearly marking what leprosy’s nerve killing illness left behind.

“No, no, this is not some sin,” Sakshi said. “I myself have gone through this.”

This conversation, shared by GFA in 201725, gives a glimpse into the despair and belief of personal guilt many leprosy patients carry.

Sakshi understood only too well the shame and grief of those she served. Leprosy was detected in her body when she was only a teenager. Dreams of living life as a normal young woman shattered with that diagnosis. Her disease barred her from visiting her neighbors or from making friends, and it even estranged her younger siblings.

“[My brother and sister] used to love me so much, but when I got this sickness, they were hating me, and they don’t want to come to me for anything,” Sakshi recalls of her early days as a leprosy patient.

Acceptance and kind words from her community were replaced with rejection and accusations. People said it was her fault she contracted leprosy, and over time, that lie took hold of her heart. Guilt and hopelessness consumed her, and she began wondering why she should endure life.

In her hopelessness, Sakshi tied a noose to hang herself.

Although Sakshi’s story does not end here, many leprosy patients’ stories end on a tragic note of despair. Whether they choose to end their lives or plod through the rest of their days alone and abandoned, the moment they discover leprosy in their body is the moment society defines them by their disease—not by their value as human beings.

GFA World calls Leprosy Patients 'Friends'

In 2007, GFA World-supported workers began ministering among leprosy patients with an aim to change that definition.

“We thought we would name the ministry differently,” says Pastor Tarik, who helped start the leprosy ministry, “where they won’t have to remember their sickness or feel the stigma of it. So while praying and discussing, we thought, ‘Let us call them “friends” because they have been created in the image of God, like us. It is only the sickness that keeps them different, but let us not make that a barrier. Let us accept them as friends.’ ”

And so, Reaching Friends Ministry began. What started in 2007 as a handful of men and women pursuing opportunities to care for outcasts of society has since expanded to minster to patients in 44 leprosy colonies. Each colony is home to as many as 5,000 patients. Through this ministry, thousands of hurting hearts have found a glimmer of love and hope to cling to.

Let us call them "friends" because they have been created in the image of God, like us.

Sakshi’s testimony proves the impact of even one kind word in the midst of isolation. Although Sakshi planned to end her life, today her story continues. On that pivotal day, her father saved her from suicide and spoke words of life into her weary soul. He told Sakshi she was a precious child and urged her to strengthen her heart through the pain and hardship.

Sakshi's feet still bear the marks of leprosy, though she is now cured.

After the conversation with her father, Sakshi gave up trying to end her own life, but she still felt alone and worried. Leprosy still disfigured her limbs and even threatened to remove one of her legs to amputation.

But then she met some GFA-supported missionaries who prayed for her and shared with her about the Great Healer. She joined them in faith and asked Jesus to heal her body. God moved on her behalf; she was miraculously healed of leprosy!

Like Sakshi, many leprosy patients are discovering that physical healing—through both prayer and medical treatment—is possible. Now, it is time for communities around the globe to be healed of the negative mindset toward those with leprosy.

Changing the Mindset Toward Leprosy

Over the passing of time, leprosy has drawn increased attention around the globe. The last Sunday in January has been observed as World Leprosy Day for more than 60 years. But while most countries have been freed from the grip of leprosy as a result of leprosy elimination programs, other areas are still high in battle against the disease.

Brazil, India and Indonesia account for more than 80 percent of new cases detected globally26, and areas of Africa also detect leprosy in high numbers. The transmission of leprosy is slowly decreasing, but more must be done, especially regarding the elimination of stigma.

These efforts have strong obstacles to overcome. The UN notes, “Historically held fears and assumptions about leprosy continue to promote the pervasive exclusion of persons affected by leprosy from mainstream efforts to include them in society and development.”

The transmission of leprosy is slowly decreasing, but more must be done, especially regarding the elimination of stigma.

In 2016, The World Health Organization launched their new Global Leprosy Strategy . Included among the increased effort to detect and care for new patients is a high emphasis on the removal of stigma and discrimination toward those with leprosy.

GFA World wholeheartedly desires to see the plight of leprosy patients improve, and its work in Asia is helping make strides in both the emotional and physical healing of those affected by leprosy.

Sisters of the Cross are specially trained to minister to the hurting, rejected and downtrodden of society—ministering to both their physical and spiritual needs in the name of Christ.

While you’ve been reading this article, national workers, including around 500 specially trained women called Sisters of the Cross, are helping care for leprosy patients throughout the Indian Subcontinent as part of GFA-supported leprosy ministry.

Sakshi herself became one of those faithful workers. After she experienced God’s healing, she dedicated her life to serving Him and enrolled in a training course. Her passion for ministry among leprosy patients soon placed her alongside other GFA-supported workers serving in a leprosy colony. Through GFA-supported Reaching Friends Ministry, she became part of bringing hope to others still trapped in the desperation she felt when she held the rope in her hand.

“Nobody is there to comfort [the leprosy patients] and to give any kind of encouragement,” Sakshi explained. “Nobody wants to love them, hug them or to come near to them to dress them. ... They have so many inner pains in their heart, because they also are human beings. They also need love, care and encouragement from other people.”

"I will become their daughter, I will become their grandchildren, and I will help them and encourage them and I will love them." —Sakshi shared about her love for the leprosy patients she serves

She and other servants of God serve these precious patients in practical ways, such as by cleaning wounds, doing housework, cooking meals and helping with personal hygiene. Through every sweep of a broom and touch of their loving, helpful hands, these workers convey how much God values His creation—even those abandoned by their own families.

“By seeing [the leprosy patients], I am thinking that I will fill the gap,” Sakshi said. “I will give that love, which they are not getting from their grandchildren and daughters… I will become their daughter, I will become their grandchildren, and I will help them and encourage them, and I will love them.”

Through love like Sakshi’s, many leprosy patients are finding new hope and lasting joy that helps carry them through their troubles.

K.P. Yohannan, founder and director of GFA World,28 wrote about his experience of witnessing leprosy ministry take place.

GFA World founder Dr. K.P. Yohannan worked alongside Sisters of the Cross to clean the wounds of leprosy patients during a trip in November 2017.

“I recently got to visit one of the many leprosy colonies where Sisters of the Cross are working,” he writes. “As I joined these Sisters of the Cross in giving out medicine and bandaging wounds, I was once again amazed by how these precious sisters embrace those afflicted by leprosy, serving them so faithfully in the name of Jesus. These leprosy patients, some without fingers or nose or ears, have faced so much rejection in their lives. But now they are finding hope, knowing that someone cares about them.”

These workers, like Sakshi, are diligently bestowing love, medical care, assistance and dignity to those suffering with Hansen’s disease. Some specialize in making customized shoes for leprosy patients, carefully measuring each individual’s feet to accommodate the sores or disfigurement the person has experienced. Other workers make warm meals for those who cannot cook—or even eat—by themselves; clean homes; wash and comb the tangled hair for those who can no longer perform even these most basic functions for themselves.

GFA-supported workers minister in whatever way is needed—here, a Sister of the Cross cleans a leprosy patient's wounds, and a man makes custom shoes for leprosy patients.

Workers serving at a GFA-supported leprosy hospital offer tender care for patients afflicted with Hansen’s disease. Beyond addressing the physical needs of medication, procedures and bandages, this hospital gives its patients emotional support, acceptance, respect and genuine concern for their holistic wellbeing. Hospital staff members routinely visit neighboring leprosy colonies to examine patients and determine who should go to the hospital for medication or treatment. They also host events to increase awareness of basic health and hygiene practices, as well as speak words of truth and life to those who feel overcome by their sorrowful plight.

GFA World Gives Leprosy Patients Food, Income-generating Gifts, Education and More

A GFA-supported Child Sponsorship Program center located within an area known for leprosy is providing free education, food, medical care and love for children from impoverished families, several of whom are touched by leprosy. While these children of leprosy patients may otherwise be rejected from schools or tolerated at a distance, they are welcomed and loved at GFA's Child Sponsorship Program.

National workers and believers in congregations in the nations GFA serves are helping break the stigma and social rejection experienced by leprosy patients. People affected by Hansen’s disease are invited into churches and homes. They are hugged. They are fed. They are shown the respect and dignity we, as Christ’s followers, believe every human being deserves.

These children, many of whose parents are leprosy patients, have the opportunity for education through their local GFA-supported Child Sponsorship Program Center.

“Jesus Himself touched [those with leprosy] and healed them,” Yohannan said in a 2017 press release29. “Jesus told us to go and do the works that He did. We, as His representatives, can show these precious people that compassion, health and healing are found in Jesus.”

On World Leprosy Day and all throughout the year, GFA-supported workers honor leprosy patients with gifts, such as blankets, mosquito nets, goats and other income-generating gifts they or their families can use to provide for themselves.

This woman was given a new blanket during a gift distribution. Leprosy patients like her have almost no resources at their disposal, and gifts like blankets are a useful blessing.

During a blanket distribution, one woman wept as she shared, “I don’t have a husband or children. I am all alone here. Nobody comes to see me. I have been staying here for more than 50 years, and now I cannot go back to my home. I am so thankful to God for those giving me this blanket and coming here and praying for me.”

Charumati, a widow who suffers from leprosy, lost her fingers and toes due to the deteriorating effects of the disease. Her son, Devan, faithfully stayed by her side, but she felt hopeless. Then she met a group of believers from a church led by GFA-supported pastor Manaar—and hope entered her life.

The pastor and believers talked kindly with her and prayed earnestly for her healing. She experienced deeper peace than she had ever known, and the news of God’s deep love and acceptance soon became an anchor for her soul.

"Jesus Himself touched [those with leprosy] and healed them... Jesus told us to go and do the works that He did."

Over the next few years, Charumati received great help and love from her newfound family in Christ. They helped her with chores like fetching water, washing clothes and making meals. They managed to raise money to provide her with new clothing and some medicine, and because of donations from GFA friends they never knew, the local church was able to provide Devan with a free sewing machine and give Charumati a warm blanket.

These are just a few of the thousands of lives impacted through Reaching Friends Ministry. GFA is grateful to be part of a global movement to bring understanding, hope and healing to leprosy patients. We believe God loves these men, women and children—whom society has degraded and labeled as “lepers” throughout history—and there is no longer any reason why anyone in the world should suffer the hardship and isolation of leprosy.